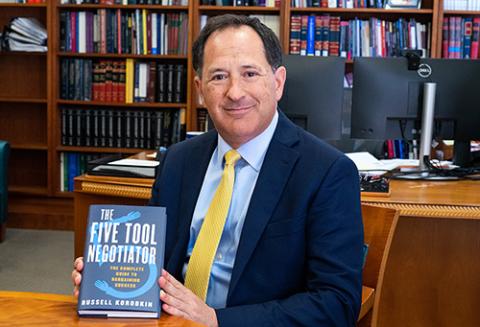

From power to persuasion, UCLA Law’s Russell Korobkin shares 5 keys to negotiation

What do creating complex financial deals, engaging with pirates on the high seas, and giving your child a bath have in common? UCLA School of Law interim dean and professor Russell Korobkin reveals that while the stakes certainly vary, each involves a negotiation.

Renowned for his scholarship and teaching in negotiation, Korobkin regularly speaks to and trains students, lawyers and businesspeople worldwide on this distinct field that incorporates a range of legal, economic, psychological and philosophical frameworks.

“Thinking about negotiation never gets boring because it involves all of these different concepts and is something that humans do all the time,” he says. “Through negotiation, we try to engage the help of others in achieving our goals. We live in a complex world where we always need the help of others. And the more complex our modern society becomes, the more important and central negotiation is to getting all of the things accomplished that we’re trying to get accomplished.”

Enter The Five-Tool Negotiator: The Complete Guide to Bargaining Success (Liveright, 2021), Korobkin’s latest book. With the everyday person in mind, Korobkin distills five major negotiation tools: bargaining zone analysis, persuasion, deal design, power and fairness norms. Korobkin is the Richard C. Maxwell Professor of Law at UCLA Law, where he has served on the faculty since 2000 and as interim dean since 2022. Here, he shares some of his expertise.

You’re a law professor and you come at this from a legal perspective, but is there any meaningful difference between negotiation in the legal context and in other arenas?

No. If you’re negotiating in a legal situation, that might slightly affect which of the different aspects of negotiation are more or less salient or critical. But the basic building blocks of how people go about negotiating to arrange their lives are really the same whether you’re engaging the settlement of a lawsuit or whether you’re just trying to get your kids to go to bed. It’s the same tools, the same process. Sure, lawyers negotiate often, but everyone needs to negotiate in their personal lives. And by the way, if you have kids or think you might, I highly recommend that you learn how to be the best negotiator you can possibly be!

What was your thinking behind boiling it all down to these five tools?

Five tools are far easier to remember than 50, which would be impossible for anybody to keep track of during a negotiation. Even so, my view is that negotiation really involves just these five tools. And the great thing is that everyone already uses all of them. Of course, some people are good at using some tools and not so great at others. Almost everybody has more of an intuitive understanding rather than a systematic, structured understanding of how these tools work. The book is aimed at giving everyone an understanding of the inherent structure of negotiation, so they can be more analytical and more conscious about what they’re doing in a negotiation and achieve better results.

So, then, how do you define better results or successful outcomes?

It’s a good question. I think there’s an objective standard for success, which would be obtaining an agreement that gives you the most possible cooperative surplus – that’s a fancy term for the most value that is possible to get in a negotiation, given that the other negotiators are also going to have their own needs and desires and goals. So, you aim to structure your agreement to generate the most joint value. And then of that joint value, you capture as large a share of it as possible, while being mindful of your need to preserve your relationship and enhance your reputation in the community so that other people want to interact with you in the future.

Is it all just a zero-sum game, then?

Not, not usually. There are some simple negotiations that are zero-sum. If I’m on vacation and buy a rug in the old city of Jerusalem, I’m going in to negotiate with the rug merchant, and then I’m never going to see him again. That might be a mostly zero-sum negotiation. But if I’m negotiating with friends about what restaurant to go to on Saturday night, that’s a situation where it’s not at all zero-sum. And there are negotiations that fall in between. In addition, if you look at the tool that I call deal design, you see how it’s possible to negotiate and structure a deal in a way that’s going to increase the benefit to both parties, by being creative and thinking outside of the box, so that both parties come away with, say, 75% of what they want.

The book uses anecdotes that come from the news and popular culture – for example, negotiating with pirates who hijack container ships – to illustrate various tactics that negotiators might use in employing the five tools. One tactic that stands out is bluffing, which often has a negative connotation. But can bluffing be valuable?

This is a nice example of negotiation at work. One of the five tools is power, which is forcing the other party to make concessions based on the threat that they otherwise won’t get what they want from you. And bluffing is one tactic negotiators sometimes use to wield that tool. Bluffing is when you threaten that you will walk away from the negotiation and not make a deal unless the other party makes a concession – knowing that, in fact, you will not walk away from the deal. There’s a risk-reward balance that you have to consider. But then there’s also the question that I think of as analytically separate, which is whether bluffing is ethical, because a bluff is fundamentally deceitful. So, there are two separate matters to consider. What is the strategic value of bluffing? And is bluffing appropriate? The book looks at this topic, and many others, in different ways.