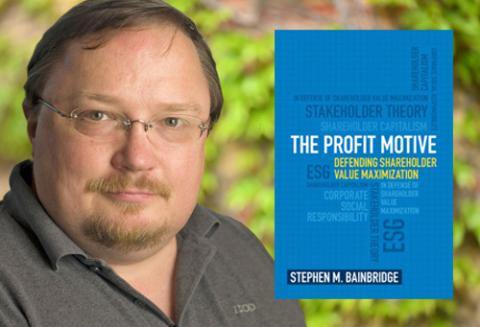

‘Elephants in the jungle’: Stephen Bainbridge on his new book about corporate purpose

As the debate over what responsibilities corporations carry in our society grows increasingly politicized, UCLA School of Law Distinguished Professor Stephen Bainbridge has entered the fray with his new book, The Profit Motive: Defending Shareholder Value Maximization (Cambridge University Press). A probing analysis of the relative merits of stakeholder capitalism and shareholder value maximization, complete with historical vignettes and innovative academic insights, the book offers an illuminating and often entertaining look at the issue.

Bainbridge is the William D. Warren Distinguished Professor of Law at UCLA Law, where he has served on the faculty since 1997, taught courses that run the gamut of business law, published more than 100 law review articles and nearly two dozen books, and won the Rutter Award for Excellence in Teaching. He consistently ranks among the most-cited legal scholars in the country and writes the popular ProfessorBainbridge.com blog. Here, he talks about The Profit Motive, “greenwashing,” and how corporations are like elephants in the jungle.

As an expert in corporate law and business policy, you could have written a book on many things – and you certainly have in your career! So, why did you write about this topic now?

There is no more fundamental public policy question in corporate law than defining the purpose of the corporation. Is it solely to generate returns for the shareholders, or does it extend to caring for stakeholders such as employees, communities, the environment and so on? This is a perennial question, of course, but it is also one that has been much in the news lately. Back in 2019, the Business Roundtable, a group of 200-odd corporate CEOs, came out with a statement of corporate purpose that embraced stakeholder capitalism: Investors show increasing interest in using ESG metrics – environmental, social, and governance – in addition to financial ones in making investment decisions. Most important, stakeholder capitalism and politics are increasingly intertwined. Populists on both the left and right increasingly oppose shareholder value maximization. What I thought the present moment required was a defense of shareholder value maximization. This is that book.

How do you define shareholder value maximization?

Shareholder value maximization argues that the goal of the corporation should be to produce sustainable long-term gains for the shareholders. It does not say that the corporation should sacrifice non-shareholder stakeholders such as employees, communities, customers or the environment in pursuit of short-term profit. To the contrary, shareholder value maximization recognizes that most situations are win-win opportunities. Doing what is good for the planet, for example, will often maximize the company’s long-run profit. But when the company is faced with a zero-sum decision, shareholder interests must come first.

Considering the hyper-politicized state of nearly everything in national and global affairs, it’s understandable that politics are increasingly intertwined with stakeholder capitalism. But do politics have any part to play in corporate law and corporate life?

Politics is inextricably linked to the debate over corporate purpose. Some commentators argue that because corporations are creations of society, they have a moral obligation to work in the best interest of society. Other commentators acknowledge that corporations do not have moral responsibilities. As a famous maxim attributed to Edward, first Baron Thurlow, puts it, the corporation “has no soul to be damned, and no body to be kicked.” Instead, they make an instrumentalist claim that our political system is so heavily polarized and, as a result, so thoroughly deadlocked that we need corporations to step up to the plate and achieve social ends that government can’t or won’t. We see this both from left-of-center and right-of-center populists. Although they disagree about the social goals corporations ought to pursue, they agree that corporations have an essential role to play in achieving their goals. Yet a third school of thought, however, finds that idea abhorrent. They think corporations are already far too powerful. Using corporations to solve major social ills would simply further empower corporations without necessarily curing those ills.

My argument is that society is better off if we ask managers to tend to their knitting instead of seeking to be social justice warriors. Consider, for example, the question of climate change, which has become a – if not the – central ESG issue. If we ask companies to comply with environmental regulations and to take into account costs such as carbon taxes, we are asking them to do things for which business executives are trained. In contrast, asking them to evaluate the adequacy of existing government policies to solve climate change and, if not, to decide how to keep global warming within tolerable limits is asking them to deal with questions way outside their wheelhouse. A core problem thus is that most directors and officers likely lack the skill set necessary to make decisions about ESG issues. If asked to resolve the more complex and difficult questions required by stakeholder capitalism, managers therefore would need to acquire much new information and expertise. As long as they lack such information and skills, asking managers to focus on such questions will inevitably distract them from ensuring that their company makes money for the shareholders.

Does the popular or lay person’s view of this issue differ greatly from that of people in academia or corporations themselves?

One of the most important themes of The Profit Motive is understanding why the Business Roundtable claimed to embrace stakeholder capitalism. Have corporate CEOs suddenly become “woke,” to use the phrase of the moment? I explore that question at some length. Ultimately, I conclude that the vast majority of corporate executives talk the ESG talk but do not walk the ESG walk. Put another way, I think most corporate talk about ESG is what might be called “greenwashing,” which means they are attempting to present a socially responsible face while actually continuing to pursue profits.

Why is the widely shared narrative that, as you write, “corporations are powerful, evil, malevolent, bad-actors intent on profit-making at the expense of the health, safety, and well-being of individuals” so prevalent?

I think it’s helpful to compare big public corporations to elephants walking through the jungle. Imagine you’re a small animal scurrying about on the jungle floor and suddenly this behemoth comes plowing through the woods. The elephant doesn’t intend to crush you or your home, but it isn’t really even aware of you. Instead, it is just trying to find something to eat. Yet, because of its massive size, it inevitably crushes anything in its way.

What other popular conceptions – or misconceptions – are at play here?

It’s important to keep in mind that the case for shareholder value maximization is not just a negative one. Pursuit of shareholder value maximization leads to more efficient resource allocation, creates new social wealth, and promotes economic and political liberty. To be sure, there will always be externalities. Just as pursuing profit is baked into the corporation’s DNA, so is externalizing costs. There is no such thing as a free lunch. The theory and evidence I recount in The Profit Motive, however, suggests that the balance comes down strongly in favor of shareholder value maximization.

-

J.D. Business Law & Policy