Cummings Book Q&A: How Lawyers Shape Social Movements in LA

An Equal Place: Lawyers in the Struggle for Los Angeles (Oxford University Press, 2021), the new book from UCLA School of Law Professor Scott Cummings, offers a close look at the lawyers who were central to Southern California’s social and labor movements from 1992 to 2008. Following Cummings’s Blue and Green: The Drive for Justice at America’s Port (MIT Press, 2018) – which documents the impact of the law on a push to improve the trucking industry at the Port of Los Angeles – An Equal Place is a broader survey that focuses on the people who, as Cummings writes, “work daily to make the city live up to its better angels and make real the dreams it presents to the world” and how “the legal profession can still serve as a wellspring for social change in a moment in which change is so desperately needed.”

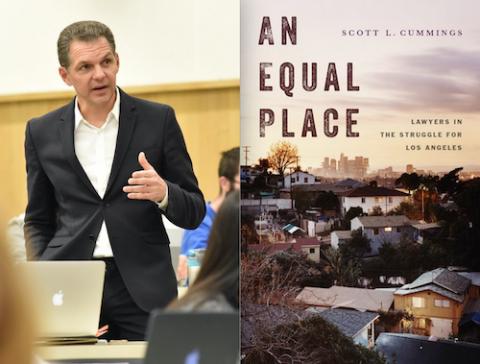

Cummings, UCLA Law’s Robert Henigson Professor of Legal Ethics, shares how he uncovered the book’s vivid stories, some lessons about lawyering, and what the future holds.

What did you learn as you conducted your research and wrote the book?

The book takes a behind-the-scenes deep dive into campaigns where lawyers helped build worker power and transform labor conditions in L.A. But they hardly did this work alone. Rather, they worked side-by-side with grassroots social movements to rewrite local laws. I interviewed scores of lawyers and activists from the period and mined original campaign documents – I spent two months in a basement at the Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy, poring over its archives. What struck me was that lawyers were working to change the city by changing how they engaged with local movements – lawyers and activists worked together, equally, on campaigns to make the city more equal. In that way, the book’s title, An Equal Place, is meant to convey a double meaning. I wanted to rethink what it meant for lawyers to “represent” clients in these large-scale efforts to change policy.

Is there a story that you uncovered that best illustrates this?

One of my favorite stories is about Thomas Saenz, a lawyer from the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, who was an architect of the campaign to end laws that made it illegal for day laborers to stand on the sidewalk to solicit work. What made the effort so successful was not just that Saenz was skilled at litigation but that he had built relations with day laborers themselves, developed a partnership with organizers, and created a strategic plan that was about shifting public attitudes toward day laborers and not just winning the case in court. It was the synergy between the litigation and organizing work that was the key to making sidewalks places that were safe for day laborers to work and support their families. [Editor’s note: Saenz has since become the president and general counsel of MALDEF.] In the book, I seek to elevate other less appreciated roles that lawyers play behind the scenes in creating new legal knowledge that contributes to the design and outcome of policy campaigns.

Would the movements have been as successful without lawyers playing these roles?

A big takeaway for me is that social struggle, at least in the American context, invariably involves law, legal processes, and legal institutions – which means that the struggle for social change almost always involves lawyers. Would L.A. have had laws like the living wage, community benefits, and clean truck program? Sure. Would they have been as sophisticated, building in provisions designed to create conditions of possibility for union organizing? No. For that, lawyers were essential. They knew what the problems with the system were and how to change law to address them.

You are an authority on legal ethics. What did you find out about ethical behavior among lawyers in movements for change?

When lawyers get involved in movements to change law and tilt power, do they act on behalf of communities or do they act in a “we know what is best for you” sort of fashion? That question of accountability is a major ethical concern of lawyering and social change. I found two interesting things. First, the lawyers I profile were all incredibly concerned about this problem and went out of their way to address it. Legal decisions were made in a collaborative and organic fashion. Second, the nature of lawyer accountability really depended on the type of legal work lawyers were doing. When they were defending immigrant workers from labor abuse, like in the garment and day labor campaigns, they had more traditional lawyer-client relationships than when they were working to shape local policy.

The book begins with the Rodney King uprising and ends with the Great Recession. But how does it offer help in predicting the future of lawyers in social movements?

If social movements are to be successful in the multifaceted process to produce sustainable shifts in culture, they have to work on changing law. But we are in such a different place – a much less equal place, in fact – than the period I describe in the book. The pandemic revealed in stark relief our deeply flawed, unequal, and divided democracy. Far from an equal place, L.A. is a microcosm, perhaps even an incubator, of broader economic division. I think a key takeaway is the power of sustained collective struggle to change law that seeks to make real the promise of American democracy. What the last several years reveals is that, although that promise is never fully achieved, we can get closer or much farther away from it. And so my modest hope for the book is that it serves as a marker of just what it takes to mount large-scale challenges to powerful systems to change law and build movements.

-

J.D. David J. Epstein Program in Public Interest Law & Policy